At first glance, the DxO One is a fag packet-sized, grey-and-black lump of indeterminate purpose that sits in your hand weighing about the same as your smartphone. Pull down on a panel on one side and it begins to reveal itself. Slide two-thirds of the way down and a slightly-inset lens is revealed. A quick tug further down makes a Lightning connector pop out for plugging into your iPhone. On the opposite side from the lens is a small LCD screen that provides basic info in use – which shooting mode you’re in and how many shots are left, for example (or your settings in manual mode). There’s also a latch hiding a MicroSD slot for storage cards and a MicroUSB port for charging. On the top is a big shutter button – and that’s it. The rest of the DxO One’s features are controlled from your iPhone. Before you can get started with the DxO One, you have to download an identically named app from the Apple App Store. The DxO One doesn’t work with Apple’s own Camera app – which is hardly surprising considering the quality and level of control DxO’s camera offers. A lof of thought has clearly gone into the design of the DxO One app – design thinking at a level you’d usually associate with Apple itself. Load the app for the first time and it provides a video tutorial on how to open up and connect the hardware to your phone. More importantly, when you disconnect the device, another video tells you how to quickly and safely pop the Lightning connector back in (which involved pulling down on the panel again, pushing it in then releasing the panel again).

Shooting with the DxO One

Using the DxO One is a wonderfully fun and easy experience – at least when you get used to it. Detached from your iPhone, it slips easily into your jeans pocket. When you want to take a shot, get it out, pop out the connector, plug the camera into your iPhone, load the app and shoot. Holding your phone and the DxO One too shoot feels a bit weird to begin with. The two parts never quite feel connected, so you have to learn where to put your hands to be able to hold the two together – as if you just hold one you worry that the connector might snap and you’ll drop one – and tap or swipe at the controls. For the first few days, you’re wondering why you can’t buy a case to hold your phone and the DxO One together. Soon, though, you get used it it and realise that any case would nullify the camera’s main merits – how easy it is to carry around with you and how quickly you can shoot with it. Or you hate it and return it. The Lightning connector between the DxO One and your iPhone can swivel so you can take shots over the heads of people at gigs or whatever. DxO would have been better off ditching the ability to swivel and having an recessed channel that the whole of the bottom of your phone slides into when you plug your phone and DxO One together for a firmer feeling connection.

A mighty, fixed lens

The 11.9mm, f1.8 lens is exceptional for its size, and behind it is a one-inch sensor – the same as you get on full-on cameras that cost around the same as the DxO One, like Sony’s RX100 III. The sensor captures 20-megapixel images, saving Raw images (or JPGs) to your MicroSD card and – unless you tell it not to – a JPG to your iPhone for quick sharing on social media (an advantage over most cameras). Even on full auto the results are (usually) noticeably better than even an iPhone 6s, especially in poor conditions. I first tried out the DxO One at a Halloween party and was really pleased with how the shots came out both outside at night and downstairs in a basement bar. However, after a few drinks the lack of image stabilisation – which your iPhone has – became apparent. And shooting Raw, I could further improve the shots at home in a way that’s just not possible with Apple’s Camera and Photos. Some people are going to be put off by the lack of a zoom lens, but that’s a sacrifice inherent in the DxO One’s core concept. I’m quite a fan of fixed lens cameras and – from snapping on our phones – most of us are comfortable with moving around and contorting ourselves to get the right shot. Your phone’s big screen – compared to most cameras – makes framing photos super easy. You also use your camera’s screen to access the DxO One’s controls. You can swipe across the screen on the back of the DxO One to change from photos to video – as you can shoot both without attaching it to your phone, but you’re essentially shooting blind and I never found a reason to do so – but everything else is reached via buttons and controls down the left and right of what turns out to be a rather brilliantly designed app. On the right are four big, thumb-sized buttons to trigger pop-out menus for capture format (more on that later), a timer, flash and shooting modes. The modes give you a full set of semi-manual and manual controls. The first set are four standard ‘scene modes’: Sports, Portrait, Landscape and Night. I didn’t find much use for these as full Auto produced the right results 99 per cent of the time – and I found it delivered better often results in low-light conditions than Night mode, which could come out underexposed (ie very dark). You can rescue these in Lightroom, but that’s no good if you want to quickly share them too. More useful are the semi-manual modes: Program AE, Shutter Priority, Aperture Priorty. Beyond this a full manual mode. Adjusting these is super-easy. On the left is a vertical set of controls to swipe up-and-down and select. Tapping on one of these – eg ISO or focus – brings up a second swipeable surface next to it to adjust the control itself. This makes changing the setting quickly intuitive and therefore fast, and there are handy icons at each end of the surface to show what the adjustments do (for example, larger and smaller apertures or a running person vs a portrait for shutter speed). As well as helping you ‘read’ the interface more quickly, they’re helpful for less experienced photographers to help them understand what these controls actually do inside the camera hardware. In the semi-manual modes, you can see the results of adjusting the exposure controls on-screen. In full-manual you have a meter (below) to tell you if you’re under- or over-exposing your images (and by how much). The DxO One camera app is probably the best camera app I’ve ever used. No touchscreen interface – no matter how slick or intuitive – can compete with the proper buttons and dials of digital SLR, as with practice you can adjust them without taking your eyes off what you’re shooting. But this really is the next best thing. You can capture images in three formats: JPG, Raw or ‘Super Raw’. In Super Raw mode, the DxO One takes four shots in quick succession, saves them as one file and then uses the processing power of your computer to combine them in a way that eliminates a lot of noise. From the evening onwards, I found that photos taken in Super Raw mode were less noisy, but I still avoided using the mode unless really necessary as Super Raw images can’t be imported directly into Adobe Lightroom or Photoshop (or Apple’s own Photos software) – you have to bring them in via DxO’s own Optics Pro software (which is available for Mac and Windows). You get a free copy of DxO Optics Pro with the DxO One – plus the DxO Connect import app and the DxO Film Pack ‘film looks’ plugin for Optics Pro, Photoshop and Lightroom. This is good value – they’d set you back £100 on your own – as long as you don’t already use something like Lightroom. Optics Pro (above) features some truly excellent photography tech – especially if you’re less experienced with photo editing or just generally in a hurry, as the automated tools like Smart Lighting and ClearView image produce great results with minimal input from you. However, it feels slow and the interface is a bit clunky next to Lightroom. The fixed lens isn’t the only compromise that DxO has made to get the One so small. There’s no flash, so you’re stuck with the iPhone’s built-in one. However, the DxO One uses a longer flash than the iPhone’s standard one, which I found gave more pleasing results. The battery life is also a lot less than you’d expect from a full-sized camera or your phone. You can be confident of the DxO making it through a full day or evening event – but perhaps not from an 11am wedding to the end of the reception. However, it charges over USB, so you can top it up using the same power bank you use for your phone.

Power comes at a price

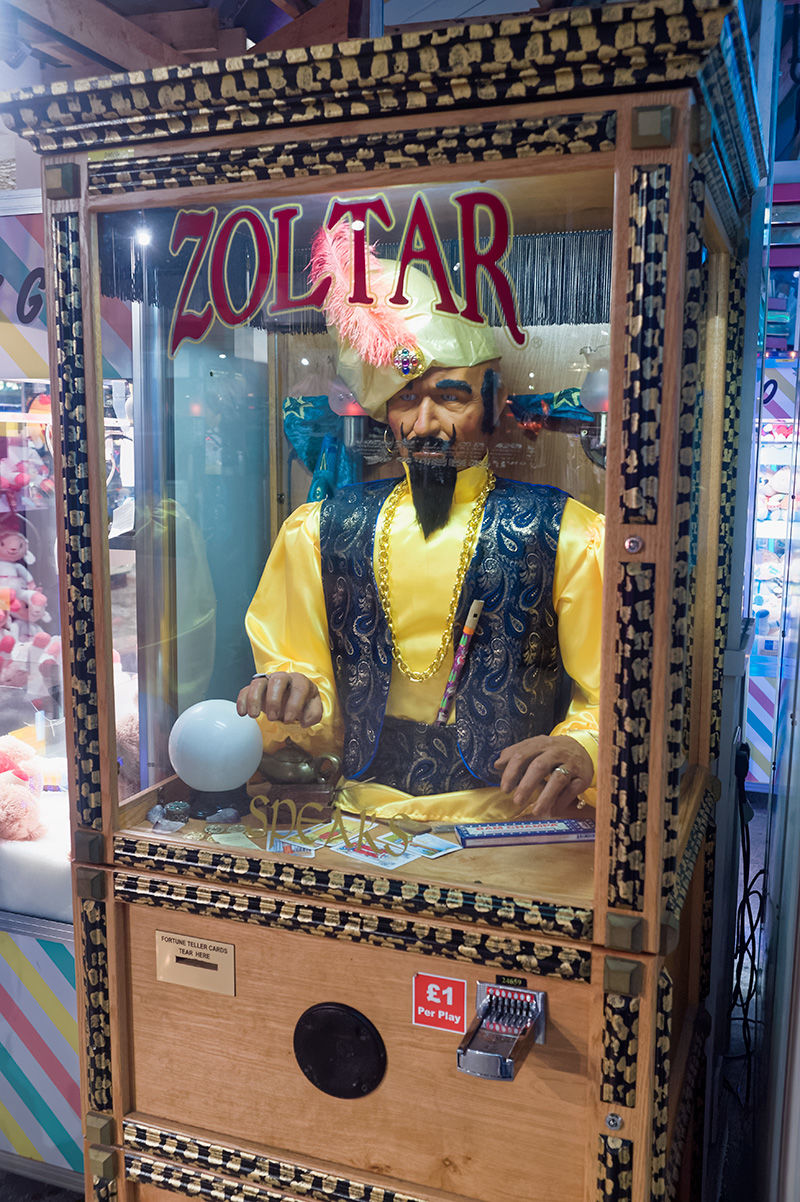

The main thing that might put you off buying the DxO One is the price. For £450 you could buy an entry-level digital SLR like the Nikon D5300 or a decent interchangeable lens camera like Fuji’s X-T10 (both with a single lens). But with the DxO One, you’re not buying a ‘proper’ camera – you’re buying convenience. What I most liked about the DxO One was that I could take really good shots at places where I’d never take a digital SLR but for which my phone’s camera would deliver less appealing results: parties, private views, weddings, theme parks, anything last minute (because I’ve generally got it in my coat pocket), anything involving my kids (because I’ve got enough to carry, thank-you-very-much) – you know, the properly fun stuff in life. I can then quickly Facebook or Tweet a couple of photos for the here-&-now, and edit the Raw files back at home for something more memorable – though I do wish I could edit Super Raw in Lightroom with having to take it through Optics Pro first.